In September 2016, The Chippendale Society in conjunction with the Leeds Art Collection Fund held a study-visit on Irish Houses and Collections. James Lomax looks back at the Irish visit and details some of the many highlights:

Carton House

Country Life, 7 & 14 Nov 1936; Stella Tillyard, Aristocrats (1995), passim; Sean O’Reilly, Irish Country Houses and Gardens (1998); John Cornforth, Early Georgian Interiors (2004), pp. 47, 208; Knight of Glin and James Peill, Irish Furniture (2007), pp. 85-6; Patricia McCarthy, Life in the Country House in Georgian Ireland (2016), passim

Our base for the first four nights was Carton House (the Mallaghan family), which has been converted into a luxury modern hotel and opened in 2006. It was the seat of the Fitzgerald family, Earls of Kildare, until 1949, with an estate of 70,000 acres. The 20th Earl of Kildare, created Duke of Leinster in 1766, the first Duchess being the celebrated Lady Emily Lennox (who begat 22 children), one of the four daughters of the 2nd Duke of Richmond and a great letter writer. Her sister Louisa married the patriot Tom Conolly of Castletown (qv), the adjoining estate. In 1739 the German born architect Richard Castle, pupil of Edward Lovett Pearce, remodelled an existing house for the 19th Earl of Kildare, creating a three-storey central block with curved colonnades and two-storey pavilions. The house was further altered in 1815 for the 3rd Duke of Leinster by Francis Johnston and Cork architect Sir Richard Morrison who converted the southern entrance front into the garden front and squared off the colonnades. The new entrance involved considerable interior alterations, notably a new screened dining room with majestic Regency plasterwork.

The Gold Saloon, originally the Eating Parlour, has some of the finest Baroque / early Rococo plasterwork in the coved ceiling, executed by Paolo and Filippo Francini, soon after their arrival from Lugano, 1739 (cf Castletown, Russborough, Curraghmore etc). The subject is the Courtship of the Gods, centering on Jupiter astride an Eagle, with six pairs of deities with busts of ancient poets in between, and 24 cupids hanging from wreaths with their legs dangling overhead. The design is taken via an engraving from Lanfranco’s painted Council of the Gods in Villa Borghese, Rome. The huge architectural organ was installed in 1857.

early Rococo plasterwork in the coved ceiling, executed by Paolo and Filippo Francini, soon after their arrival from Lugano, 1739 (cf Castletown, Russborough, Curraghmore etc). The subject is the Courtship of the Gods, centering on Jupiter astride an Eagle, with six pairs of deities with busts of ancient poets in between, and 24 cupids hanging from wreaths with their legs dangling overhead. The design is taken via an engraving from Lanfranco’s painted Council of the Gods in Villa Borghese, Rome. The huge architectural organ was installed in 1857.

The Chinese or India Paper Drawing Room was created by Emily with the arrival of the Chinese paper in 1759. It was cut into a variety of panels, cartouches and ovals depicting exotic palaces and gardens, birds, flowers, waterfalls and groups of elegant figures. These are framed with Chinese borders and set against a background Prussian blue re-used wallpaper from Leinster House, Dublin. The walls are bordered with Rococo gilding and above the chimney is a spectacular Chinese mirror with branches, possibly executed by John Houghton and John Kelly, virtuoso Dublin carvers who hosted Thomas Johnson on his sojourn in Dublin. A drawing in the Leinster archives (attributed to the architect Isaac Ware) suggests the branches may have been for china vessels etc.

The Chinese or India Paper Drawing Room was created by Emily with the arrival of the Chinese paper in 1759. It was cut into a variety of panels, cartouches and ovals depicting exotic palaces and gardens, birds, flowers, waterfalls and groups of elegant figures. These are framed with Chinese borders and set against a background Prussian blue re-used wallpaper from Leinster House, Dublin. The walls are bordered with Rococo gilding and above the chimney is a spectacular Chinese mirror with branches, possibly executed by John Houghton and John Kelly, virtuoso Dublin carvers who hosted Thomas Johnson on his sojourn in Dublin. A drawing in the Leinster archives (attributed to the architect Isaac Ware) suggests the branches may have been for china vessels etc.

Although no indigenous furniture survives in the house Emily’s correspondence suggests she was deeply concerned with its furnishings, ordering taffeta, chintzes, and wallpapers via London and Dublin. Drawings in the archives show designs for rococo pier glasses, girandoles, a bed etc, attributed to the Dublin furniture maker Richard Cranfield.

Castletown ((OPW and the Castletown Foundation)

Maurice Craig and the Knight of Glin, ‘Castletown, Co Kildare I – III’, Country Life 27 March, 3 and 10 April 1969; Giles Worsley, ‘Castletown House, Co Kildare’, Country Life 17 March 1994; Stella Tillyard, Aristocrats (1995); Sean O’Reilly, Irish Country Houses and Gardens (1998); John Cornforth, Early Georgian Interiors (2004); Kinght of Glin and James Peill, Irish Furniture (2004); Jeremy Musson, ‘The Epitome of Ireland’, Country Life 27 July 2016; Patricia McCarthy, Life in the Country House in Georgian Ireland (2016), passim

At Ireland’s earliest and grandest Irish Palladian house we had the privilege of being led by Christopher Moore, formerly curator and now Chairman of the Castletown Foundation. The mansion was begun in 1722 for William Conolly, a self-made millionaire who amassed vast estates as a result of the Williamite wars, becoming Speaker of the Irish House of Commons. The 11-bay central block of white stone with alternating pedimented and segmental windows is based on Palazzo Farnese, Rome, and is attributed to Alessandro Gallilei (architect of St John’s Lateran, Rome), but it was probably executed by the young prodigy Edward Lovett Pearce (architect of the Irish Parliament Building, now Bank of Ireland), with much input from Conolly himself, Bishop Berkeley, and Thomas Burgh, Surveyor of the Royal Works. All the materials were intended to be of Irish provenance, ‘an epitome of Ireland’. William Conolly was the only Irish ‘gentleman’ subscriber to Chippendale’s Director.

It was not completed until it was inherited by Conolly’s great nephew Thomas Conolly, who married Lady Louisa Lennox, one of the four daughters of the 2nd Duke of Richmond and whose sister Emily was married to the Duke of Leinster at Carton, the adjoining estate. They installed a spectacular new staircase, employed Filippo Francini for the fine late Rococo plasterwork (dated 1759), and laid out new reception rooms in the style of Sir William Chambers, executed by his pupil Simon Vierpyl.

Castletown remained in the ownership of the Conollys and their descendants until 1965, when it was bought by the Hon. Desmond Guinness who managed to save some of its original contents. Its ongoing restoration was initiated by the Irish Georgian Society and the Castletown Foundation. In 1994 it was taken over by the OPW.

The Gallery is unusually situated at the top of the stairs on the first floor and used as an all-purpose informal living room from the beginning. It was transformed in the mid-1770s with painted ‘Pompeian’ decoration chosen by the childless Louisa and her disgraced sister Lady Sarah Bunbury with an iconography around melancholy aspects of marriage (see Aristocrats, pp 207-9) by Thomas Riley, taken from the Vatican Loggie, Hamilton’s Vases, Montfaucon etc., large mirrors, brackets with busts etc

The Print Room, is the most celebrated one in Ireland, entirely arranged by Louisa and Sarah.

There is some significant and indigenous Irish and English furniture: Lady Louisa’s bureau (a close variation of which is at Temple Newsam); a Charles Clay clock; a japanned cabinet painted by William Conolly’s wife; Kentian pier tables and glasses in the Green and Red Drawing Rooms and a set of three fine Rococo pier glasses in the Dining Room, all attributed to the Dublin carver Richard Cranfield. The suite of Irish ‘Chinese Chippendale’, with blind fret legs and arms, are en suite with sofas whose back rails appear to have been ‘straightened’ later in their history. Another fine Irish suite, originally at Headfort House, retains its original English Soho floral tapestry.

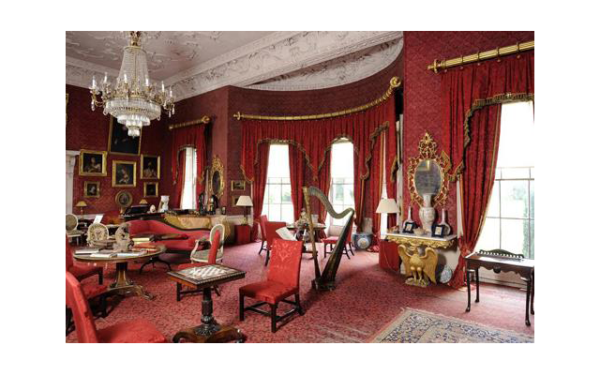

Conservation work is ongoing at Castletown: we arrived on a day when a small team of conservators had just arrived to begin work on cleaning and consolidating the mid-19th century red damask hangings in the Red Drawing Room. Christopher has hopes of reinstating replica bookcases in the Gallery.

There are many 18th century descriptions of Castletown which was much visited. The Duchess of Northumberland (1763): ‘…half finished…closet in very pretty taste’; Lady Shelburne: ‘ very magnificent…antechamber with pale green damask…drawing room in damask of four colours…a Print Room on ye palest paper I ever saw and pretties of its kind…very pretty dressing room fitted up in French taste hung with white damask and portraits tied with knots of purple and silver ribbons…house full of cabinet work of inlaid wood made in London and pieces of French and old china…’

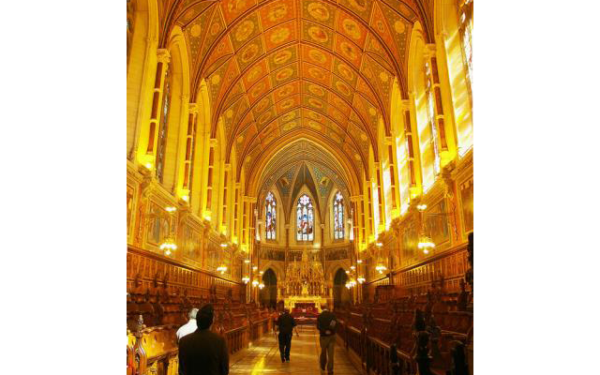

Chapel of the Royal College of St. Patrick, Maynooth.

Roderick O’Donnell, ‘The Church Trimphant’, Country Life, 16 April 2014

Here we were the guest of Professor Terence Dooley, Director of the Centre for the Study of Irish Houses and Estates at the Universty of Ireland, Maynooth, whose department has taken the lead in researching the history of Irish country houses.

The college was established with royal approval in 1795 for the formation of Catholi c clergy, hitherto trained on the Continent. Barrack – like collegiate buildings were erected around St. Joseph’s Square. In 1845 Peel passed the controversial Maynooth Grant Act granting £30,000 for building works. AWN Pugin was appointed and provided designs for new buildings. His son EW Pugin continued with JJ McCarthy ‘the Irish Pugin’, to include the library, refectory etc.

c clergy, hitherto trained on the Continent. Barrack – like collegiate buildings were erected around St. Joseph’s Square. In 1845 Peel passed the controversial Maynooth Grant Act granting £30,000 for building works. AWN Pugin was appointed and provided designs for new buildings. His son EW Pugin continued with JJ McCarthy ‘the Irish Pugin’, to include the library, refectory etc.

After lunch in Pugin’s refectory, we visited the Russell Library where a special display of manuscript books of hours, rare printed books of hours, incunabula and cuneiform tablets had been very kindly arranged for us. We proceeded to the spectacular Chapel where we were led by Professor Sheridan who gave us a full account of the building and iconography. The foundation stone was laid in 1875 and the building followed much of Pugin’s original plan and including the detached tower and second tallest spire in Ireland. The collegiate style interior with room for 450 seminarians began in 1887 under William Hague of Dublin. It is probably the finest and richest polychromatic High Victorian interior in Ireland, without any suggestion of Aesthetic Movement or Celtic Revival, its total cost being over £40,000. It was recently restored to a very high standard.

From here we drove to Hamwood (Mr Charles Hamilton).

Jeremy Musson, ‘Hamwood, Co Meath’, Country Life 23 Feb 2006, pp71 – 75

This is a modest Palladian but delightful house completed in 1764, for Charles Hamilton, the agent for the Carton estate (a job inherited by subsequent heirs until 1975). It has an unusual plan of a central block flanked with curved passages ending in octagonal pavilions. The ground floor has a double drawing room-cum-library separated by an arch. The ensemble has remained largely and the family collection includes much indigenous Irish furniture including some fine rococo mirrors, notably an example derived from an engraving by Pierre Babel over the main chimneypiece, and another fine oval palm-wreath encrusted pier glass at the library end. There are Irish Chippendale chairs, and marquetry cabinets attributed to William Moore (probably the most significant and prolific neo Classical cabinet maker in Dublin, who had trained with Mayhew and Ince and returned to Ireland in 1777, supplying the gentry in the new style). Upstairs there are numerous satirical drawings by Caroline Hamilton, née Tighe, depicting Dublin life in the early post Union era. The Dining Room chimney had a rare example of an inset Wedgwood basalt plaque on the rail, of the so-called Death of Achilles (another example at Temple Newsam).

Next day at Newbridge (Fingal County Council and the Cobbe Family) we were most fortunate to be hosted by Alec Cobbe, who had returned from London especially to be with us, together with his archivist Cathal Dowd- Smith.

John Cornforth, ‘Newbridge, Co Dublin’, I and II, Country Life, 20 and 27 June 1985; Gervase Jackson Stops, ‘Newbridge Restored’, Country Life, 18 Feb 1988; Mildred Archer and Gervase Jackson Stops, ‘Mr Cobbe’s Cabinet of Curiosities’, Country Life, 10 March 1988; Alec Cobbe and Terry Friedman, ‘New bridge, Co Dublin’, Country Life, 4 Oct 2001; Terry Friedman, ‘I consulted several curious architects’, Country Life, 24 Jan 2002; Alec Cobbe and Terry Friedman, James Gibbs in Ireland (2004)

Newbridge is an extraordinarily interesting and well documented house and family. It was built by Charles Cobbe from Winchester, Hants, who rose to become Archbishop of Dublin. His hopes for a big Palladian mansion designed by James Gibbs were dashed when he was passed over as Archbishop of Armagh and Primate, so he had to be content with a reduced design by Gibbs (1746-9), confirmed after considerable new research by Alec Cobbe and the late Terry Friedman. Cobbe was succeeded by his son Thomas and talented daughter-in-law Lady Betty who added a unique drawing room-cum-picture gallery to house theirs and the archbishop’s celebrated collection of Dutch and Italian Old Masters. Much of this was collected for them by Rev. Matthew Pilkington, the estranged husband of the notorious Letitia (‘Queen of the Wits’). There is much fine plasterwork of the 1760s by Richard Williams. Much original and indigenous furniture survives from the 18th century and Regency, including a fine pair of side tables in the Dining Room, a suite of French style white and gold chairs, a rare ‘strawberry wood’ table, and a secretaire-cabinet by Christopher Hearn who supplied over £200 of furniture in the early 1760s, a pair of fine late Rococo pier glasses signed by James Robinson, sconces and frames by Richard Cranfield (cf Castletown), pier tables by John Wisdom. The drawing room still houses its original flock paper, curtains and carpet from the 1820s, supplied by Mack, Williams and Gibton. The unique Cabinet of Curiosities or Museum was mainly formed from the collection of the early 19th century Indian nabob Thomas Cobbe and his Muslim wife.

In 1987 the miraculously preserved house and demesne were acquired by Fingal County Council, with the family retaining the right to live there. The picture collection of the Cobbe Collection Trust is divided between here and Hatchlands, Surrey.

After a splendid lunch in an open marquee in the Rose Garden we drove north to Beaulieu, near Drogheda, the family home of Cara Konig-Brock.

Sean O’ Reilly, Irish Houses and Gardens (1998); Knight of Glin and James Peill, Irish Furniture (2007), pp. 38-40; Roger White, ‘The Fruits of Public Service’, Country Life, 28 Oct 2015.

‘One of the most important late 17th and early 18th century houses in Ireland’. The design is based on the classic mid-late 17th century Anglo-Dutch style (Coleshill, Clarendon House, Honington, Groombridge, Belton etc). It was formerly thought to have been built in the 1660s for Sir Henry Tichborne, the Protestant defender of Drogheda in the Williamite Wars, and to have been confiscated from the Catholic Plunket family. It is more likely to have been built by his grandson, Lord Ferrard c1710, by the architect/builder John Curle. It has a fine double height hall with superbly carved trophies in the tympana above the doorcases, in the French baroque style of the Tabary brothers. These were Huguenot virtuoso carvers employed by the Duke of Ormond at Kilmainham Royal Hospital especially in the chapel. There may be a link between them and Edward Pearce, the carver of Sudbury, Derbys etc. There were also a pair of elaborately scrolling wall plaques centred on mask heads which may well have been intended as sconces. Elsewhere there was much fine robust plasterwork and a number of distinctly Irish pieces. The ambiguous but amatory subject of the trompe d’oeil ceiling painting in the present Drawing Room suggests it may originally have been the bedroom of the principal apartment. There were two (possibly three) fine 19th century heraldic scagliola tables from the Darmanin workshops in Malta reflecting a period when an heiress brought new wealth into the family and possibilities for travel. The walled garden was delightful, full of late summer flowers, sloping down to the River Boyne, and contained an unusual pedimented shed with tree-trunk columns illustrating the Abbé Laugier’s first principles of classical architecture.

Part 2 of this Report will follow shortly.